How Fashion Historian Teleica Kirkland Is Transforming What We Know About Clothing From the African Diaspora

|

Photo graphic by Alanna Bass.

Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

|

The founder of the Costume Institute of the African Diaspora is preserving Black history in a field where it's been erased.

From the effortlessly stylish aunties who rock matching wax-print top and bottoms like they're going out of style (they never will), to the urban youth who create just about every street-wear trend—clothing is a central part of cultural expression for people of African descent. While our penchant for style is something many of us recognize within our own community, the academic world has virtually ignored the contributions of Africans to the history of global style. For the average fashion historian, their scope of research begins and ends in the West.

Given that clothing tells the story of how people live, work and identify themselves—excluding Africa and its diaspora from the discussion undermines its cultural influence and threatens the push for more robust historical documentation of African people. If the rise of haute couture marked a period of newfound creativity and wealth in France, isn't it also worth understanding, for instance, how fashion changed in various African countries both before and after the liberation movements of the 1960s?

This is where Teleica Kirkland's work comes in. In 2011, Kirkland, a professor at the London College of Fashion, founded the UK-based Costume Institute of the African Diaspora (CIAD), a "growing resource hub" for knowledge sharing around African clothing and dress.

|

| Teleica Kirkland(Photo courtesy of Teleica Kirkland.) |

With clothing as the catalyst, Kirkland hopes to answer a much larger question about global Black identities: "How have [Africans] taken their adornments, their clothing, their fashions and used it to define and identify themselves wherever they find themselves?"

Becoming a Fashion Historian

While Kirkland is a decorated academic, who has run her own fashion company, curated museum exhibitions and worked with the likes of Vivienne West-wood, her journey as a fashion historian began long before she had the academic qualifications or even the language to describe what exactly she wanted to do. In 2007, she curated a solo exhibition around the Yoruba Orishas and wanted to know why the supreme deity Oshun is commonly portrayed wearing ethereal, yellow garments. When she tried to find the answer, she was stunned by the lack of definitive sources available.

"I was like, there's got to be some place in the world," says Kirkland. "We have the Victoria and Albert Museum [in London], and there's the Costume Institute—or even the Costume Institute at the Met. And I was like, how can there not be something about African Diaspora or African clothing and costume?"

She decided to fill the gap. "I started to try and put something together on the basis that some kind of collation of our dress history, costume history, has to exist in the world," she says. "I didn't realize at that time what a massive undertaking that was."

For Kirkland, the desire to understand clothing also stemmed from the role it's played in her Jamaican heritage. "Clothing and dress has always been in my history," says Kirkland. "My mothers, grandmothers, aunts, always made clothes, so that was just something that was in my natural history anyway."

This led her down an academic path that she might have otherwise been shut out of on account of her Black, working class background. When she started out, there weren't many fashion historians from the same demographic that she could model her career after.

"I didn't know that there were things like curation, fashion curators, fashion historians, costume historians, research," explains Kirkland. "I didn't know any of that. I didn't even have that vocabulary. I came to it because I wanted to know the information, and I suppose, wanting to know the information then led me on to speak to other people who were like: Oh well, you could apply for this funding to do this and this funding to do that."

Laying the Ground for New Knowledge

Kirkland earned a Master's in History and Culture of Fashion in 2015, and is currently completing her PHD. As she's gained status in her field, she's made it her priority to represent an African-centric point of view in a space that has historically undervalued it. It's been no small task. She describes having to explain basic concepts such as "color-ism" to a mostly white class when teaching on the legacy of 18th century Quadroon Balls in Louisiana, and a similar instance that occurred when she gave a lecture at one of the world's top institutes for costume design.

"I've got all these seemingly academics and older people who have been in this field [for years] scribbling down, tapping away, making notes," she says."I had to pause myself—I'm like hold on, why is everyone making notes?" Her audience, despite their status and longevity in the field, were unfamiliar with the topics being discussed, and it was clear why. "Of course they only operate within a European context. They know about European dress. They might even be able to touch on East Asian dress and clothing," she adds. "But they know nothing about the Americas or Africa or anything like how this affects people and why it affects people."

Understanding Fashion Across the African Diaspora

While "laying the ground as you walk or laying the train tracks as the train's coming," has been challenging, Kirkland stresses that the work itself has proven rewarding. In many ways, it's opened up a new world for the academic, and she speaks passionately when reflecting on it. She began her research with travels across the Caribbean, which expanded her understanding of the role clothes play in its environmental context—perhaps in a way that being in a classroom couldn't.

"The history of clothing is not preserved the way history of clothing is preserved in a European context or in the American context," says Kirkland. "Everything in the Caribbean is used until it can't be used again, which means it's disintegrated. But then, even that history is interesting: trying to explain how a dress becomes a skirt, a shirt becomes a baby's nappy or a baby's outfit, then becomes a rag, and then becomes something else until there's nothing left of it—this explains the context of how people relate and engage with their clothing in that particular way."

She's visited kente weaving communities in Toso and Kumasi in Ghana, and been intrigued by the fact that the ubiquitous cloth is made mostly by men. She studied the research of fellow scholar and friend Lucille Junkere, about diasporic links between Abeokuta Nigeria, the home of indigo-dyed adire cloth, and the city by the same name in Jamaica, where it is believed that enslaved people continued in the tradition of textile-making.

The research she's done has brought her back to the same personal history that set the foundation for her career path. Her most cherished clothing item is her grandmother's 1950's-era wedding dress that, perhaps, as some sort of metaphorical sign, has stood the test of time. "Moths had a good go on it, but they didn't eat it—which I found really interesting."

While academia's systemic blind spot towards Black achievement has made her job more demanding, Kirkland insists it's been worth it. "There have been challenges," she says. "But it's not challenging enough to make me throw in the towel and be like, you know what, suck it."

Instead, she continues to expand the scope of her work through CIAD. The institute was set to hold its second annual biennial this Spring, focusing on the production of fabric across the diaspora, but it's been postponed till October due to the corona-virus outbreak. Ultimately, CIAD's mission is one that's of critical importance to just about anyone invested in preserving African cultural heritage, whether that be through the study of clothing, music, art or any other medium. "The whole push towards decolonizing is basically trying to get the other side of the story," she says. "We've understood the European context of history for... forever actually. This is really [about] providing another side to the context of history."

While Kirkland is a decorated academic, who has run her own fashion company, curated museum exhibitions and worked with the likes of Vivienne West-wood, her journey as a fashion historian began long before she had the academic qualifications or even the language to describe what exactly she wanted to do. In 2007, she curated a solo exhibition around the Yoruba Orishas and wanted to know why the supreme deity Oshun is commonly portrayed wearing ethereal, yellow garments. When she tried to find the answer, she was stunned by the lack of definitive sources available.

"I was like, there's got to be some place in the world," says Kirkland. "We have the Victoria and Albert Museum [in London], and there's the Costume Institute—or even the Costume Institute at the Met. And I was like, how can there not be something about African Diaspora or African clothing and costume?"

She decided to fill the gap. "I started to try and put something together on the basis that some kind of collation of our dress history, costume history, has to exist in the world," she says. "I didn't realize at that time what a massive undertaking that was."

|

| West Indies Guadeloupe carnival groups.Photo by Jean-Marc LECERF/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images |

This led her down an academic path that she might have otherwise been shut out of on account of her Black, working class background. When she started out, there weren't many fashion historians from the same demographic that she could model her career after.

"I didn't know that there were things like curation, fashion curators, fashion historians, costume historians, research," explains Kirkland. "I didn't know any of that. I didn't even have that vocabulary. I came to it because I wanted to know the information, and I suppose, wanting to know the information then led me on to speak to other people who were like: Oh well, you could apply for this funding to do this and this funding to do that."

|

| Grandassa Models at the Merton Simpson Gallery, New York (c. 1967) by Kwame Brathwaite.(Photo courtesy of the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles.) |

Kirkland earned a Master's in History and Culture of Fashion in 2015, and is currently completing her PHD. As she's gained status in her field, she's made it her priority to represent an African-centric point of view in a space that has historically undervalued it. It's been no small task. She describes having to explain basic concepts such as "color-ism" to a mostly white class when teaching on the legacy of 18th century Quadroon Balls in Louisiana, and a similar instance that occurred when she gave a lecture at one of the world's top institutes for costume design.

"I've got all these seemingly academics and older people who have been in this field [for years] scribbling down, tapping away, making notes," she says."I had to pause myself—I'm like hold on, why is everyone making notes?" Her audience, despite their status and longevity in the field, were unfamiliar with the topics being discussed, and it was clear why. "Of course they only operate within a European context. They know about European dress. They might even be able to touch on East Asian dress and clothing," she adds. "But they know nothing about the Americas or Africa or anything like how this affects people and why it affects people."

|

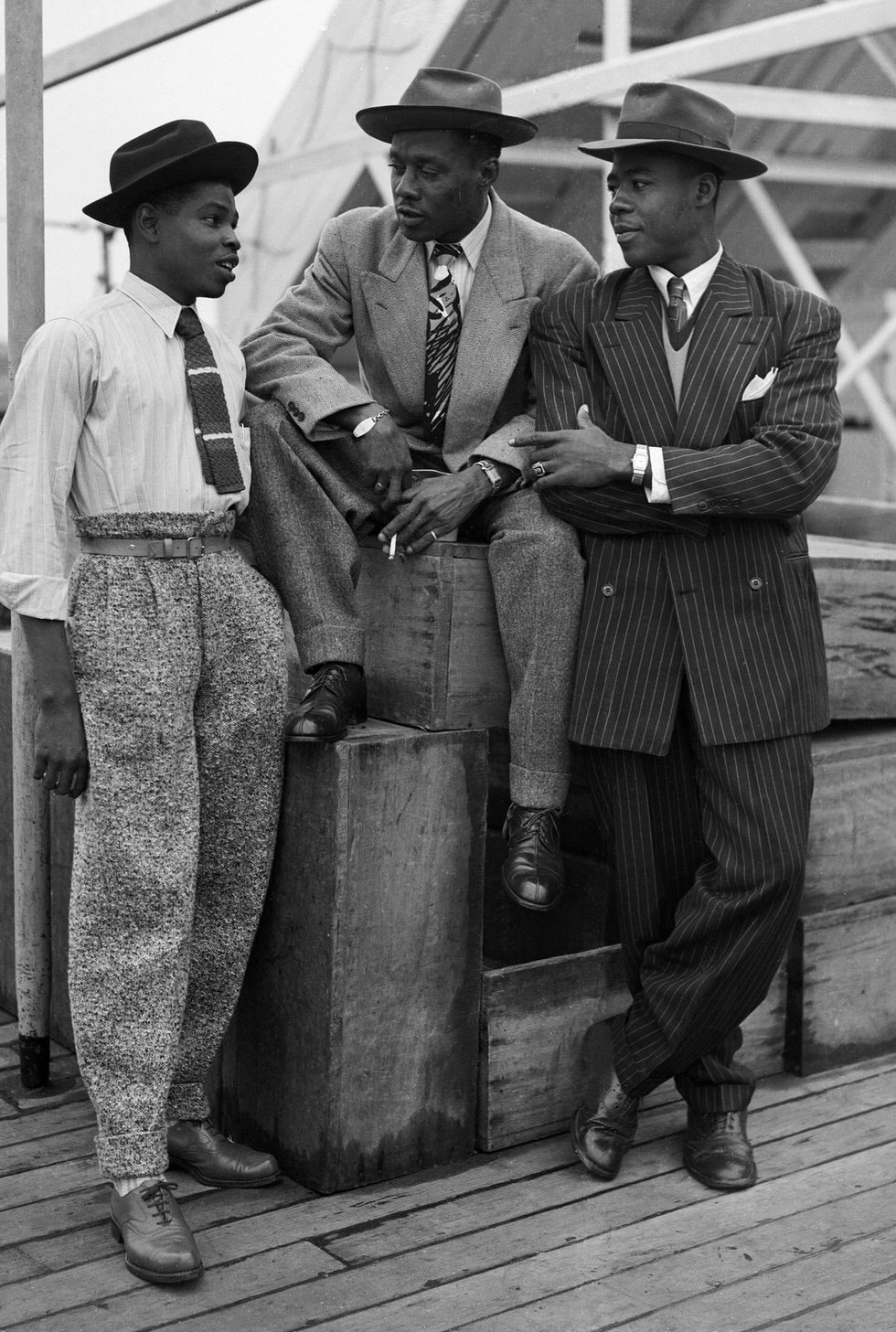

| Three Jamaican immigrants (left to right) John Hazel, a 21-year-old boxer, Harold Wilmot, 32, and John Richards, a 22-year-old carpenter, arriving at Tilbury on board the ex-troopship 'Empire Windrush', dressed in zoot suits and trilby hats.(Photo by Douglas Miller/Getty Images) |

While "laying the ground as you walk or laying the train tracks as the train's coming," has been challenging, Kirkland stresses that the work itself has proven rewarding. In many ways, it's opened up a new world for the academic, and she speaks passionately when reflecting on it. She began her research with travels across the Caribbean, which expanded her understanding of the role clothes play in its environmental context—perhaps in a way that being in a classroom couldn't.

"The history of clothing is not preserved the way history of clothing is preserved in a European context or in the American context," says Kirkland. "Everything in the Caribbean is used until it can't be used again, which means it's disintegrated. But then, even that history is interesting: trying to explain how a dress becomes a skirt, a shirt becomes a baby's nappy or a baby's outfit, then becomes a rag, and then becomes something else until there's nothing left of it—this explains the context of how people relate and engage with their clothing in that particular way."

She's visited kente weaving communities in Toso and Kumasi in Ghana, and been intrigued by the fact that the ubiquitous cloth is made mostly by men. She studied the research of fellow scholar and friend Lucille Junkere, about diasporic links between Abeokuta Nigeria, the home of indigo-dyed adire cloth, and the city by the same name in Jamaica, where it is believed that enslaved people continued in the tradition of textile-making.

The research she's done has brought her back to the same personal history that set the foundation for her career path. Her most cherished clothing item is her grandmother's 1950's-era wedding dress that, perhaps, as some sort of metaphorical sign, has stood the test of time. "Moths had a good go on it, but they didn't eat it—which I found really interesting."

|

| Kirkland's grandmother Florence Palmer (nee) Raymond, March 1963(Photo courtesy of Teleica Kirkland.) |

Instead, she continues to expand the scope of her work through CIAD. The institute was set to hold its second annual biennial this Spring, focusing on the production of fabric across the diaspora, but it's been postponed till October due to the corona-virus outbreak. Ultimately, CIAD's mission is one that's of critical importance to just about anyone invested in preserving African cultural heritage, whether that be through the study of clothing, music, art or any other medium. "The whole push towards decolonizing is basically trying to get the other side of the story," she says. "We've understood the European context of history for... forever actually. This is really [about] providing another side to the context of history."

Comments

Post a Comment

You must be logged in to comment